Long regarded as a backwater in Southeast Asia, Laos is famous for its soporific vibe. So much so that the acronym in the country’s official title — Lao PDR — is often mangled from People’s Democratic Republic to Please Don’t Rush. But the new railway is encouraging a faster pace.

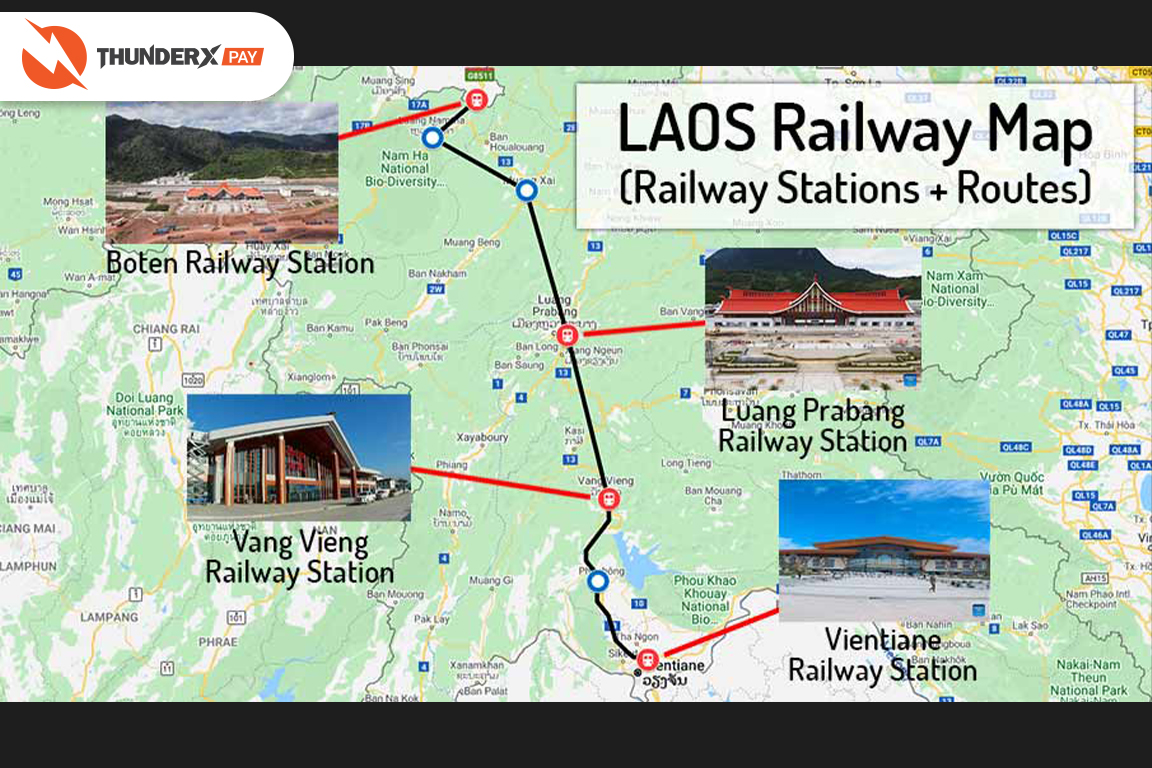

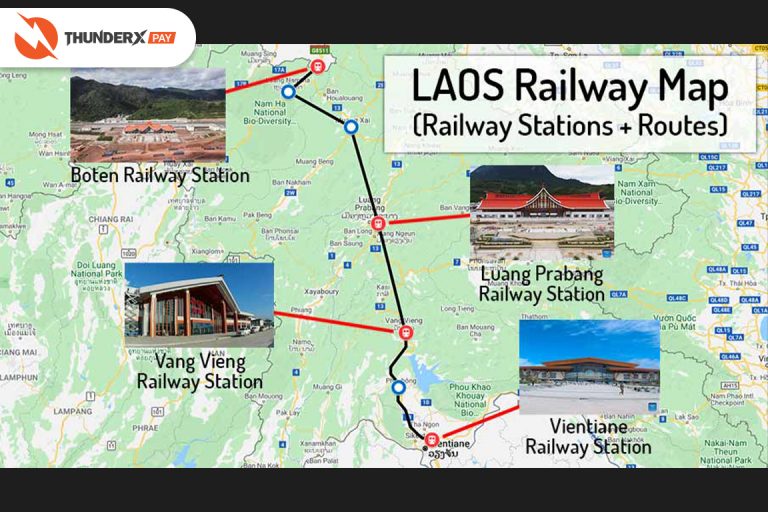

The train links Vientiane with top visitor destinations like Vang Vieng — a karst-studded playground famous for its adventure options — as well as Luang Prabang, the country’s charming former royal capital, and Luang Namtha, with its patchwork of hill tribe minorities and jungle-clad mountains — perfect for trekking and eco-tourism. And it is a potential godsend for a tourism industry that desperately needs visitors in the wake of the pandemic.

Indeed, the semi-high-speed route now opens between Vientiane, just across the Mekong River from Thailand, and Boten, on the border with Yunnan Province in China, is not just revolutionary for Laos: it’s as advanced as any railway infrastructure seen in Southeast Asia until now.

The new China-Laos passenger and freight railway, serviced by Electric Multiple Unit (EMU) trains, stretches 1,035 kilometers (643 miles) and was designed to link Vientiane with Kunming, the capital and largest city in China’s Yunnan province. It will eventually connect a total of 45 stations between both countries, of which about 20 will provide passenger services.

Passengers are currently unable to travel through to Yunnan in China though as the latter has yet to open to international tourism. (Laos reopened in May 2022.) For now, travelers can experience 422 kilometers of rugged, mountainous Laos landscapes as the train hits speeds of up to 160 kph (about 100 mph) and spears through 75 tunnels and over 167 bridges and viaducts.

Part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

The new railway, which will eventually link Beijing with Bangkok and Singapore in the decades to come if all goes to plan, is a crucial component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the vast infrastructure development program launched in 2013 to expand Beijing’s influence.

Funding for it came mainly from China — although Laos stumped up a fair portion: a financial outlay that looks increasingly precarious considering its growing debt plight. The cost of the railway has reportedly contributed to a US$480 million increase in Lao debt to the Chinese Export-Import Bank, fueling fears of dependence on its giant neighbor to the north. Given its provenance, it’s no surprise that the railway has a Chinese feel. Stations are impressive, but austere affairs like the ones found in China.

Inside Vientiane station, for instance, there are no food hawkers — those traditional mainstays of train travel in Southeast Asia. Just rows of seats, toilet facilities, a couple of vending machines, and a hot and cold-water dispenser to fill up drinking bottles or cups of instant noodles. Signs around the stations feature Chinese and Lao script, but there’s little information available in English.

The train itself, which seats 720 people in first- and second-class carriages and plies the route between Vientiane and Boten twice daily, boasts white, red, and blue stripes, the colors of the Laotian flag. But overt local influence ends there.

Overall, the train favors function over form. There’s no food trolly service or dining car, which makes me grateful for the emergency rations I picked up at a sandwich stand near my hotel in Vientiane. But the seats are comfortable, there’s plenty of legroom and space in the overhead luggage racks for the heftiest of suitcases or backpacks, and power points underneath the seat supply juice for phones and laptops.

As the train arrows north, we kick back and watch the emerald-green landscapes unfold outside the train window. On the day of my travels, the train is virtually free of foreign tourists: a consequence of the current low tourist footfall in Laos and it being the height of the rainy season.

But challenges have prevented the railway from making a flying start with tourists. For now, tickets can only be purchased in cash within three days of travel (an online system is reportedly in the works). Complicating matters further is the fact you can only snap up tickets at Laos-China Railway stations — not so easy given their locations are a fair distance from the center of towns like Vientiane, Luang Prabang, and Luang Namtha — or a tiny handful of non-railway ticket offices.

Despite these wrinkles, it seems inevitable that a mode of transport that links some of the country’s top draws in double-quick time will eventually prove a hit with travelers: even more so when China finally opens its borders and visitors flock in from the north.

It’s fair to ask whether the railway is a luxury that the Southeast Asian country can ill afford. But there’s no doubt it’s a boon for many Lao people who have never had the chance to move around their country as freely or speedily.

“I used to dislike traveling home to see my family,” says Ying as we approach Na Teuy station: the jumping-off point for Luang Namtha city and its surrounding communities. “But now I hope to be able to see them at least a couple of times each year.”

With that, she gets off the train. Outside the station, the countryside chariot awaits in its dust-coated, smoke-sputtering glory to whisk her group into the family village. Judging by the smile on her face, any residual anxiety about the long-awaited reunion appears to have vanished.

For Ying, rare trips home have always been about the destination rather than the journey -the latter being something to endure. But, for once, she appears to have enjoyed the ride.

Published 30/01/2023

By Michael Saichuk