We assume that Russian gas flows to Europe via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline will fluctuate between zero and 20% capacity in the coming months, resulting in a recession in Europe in the winter of 2022/23.

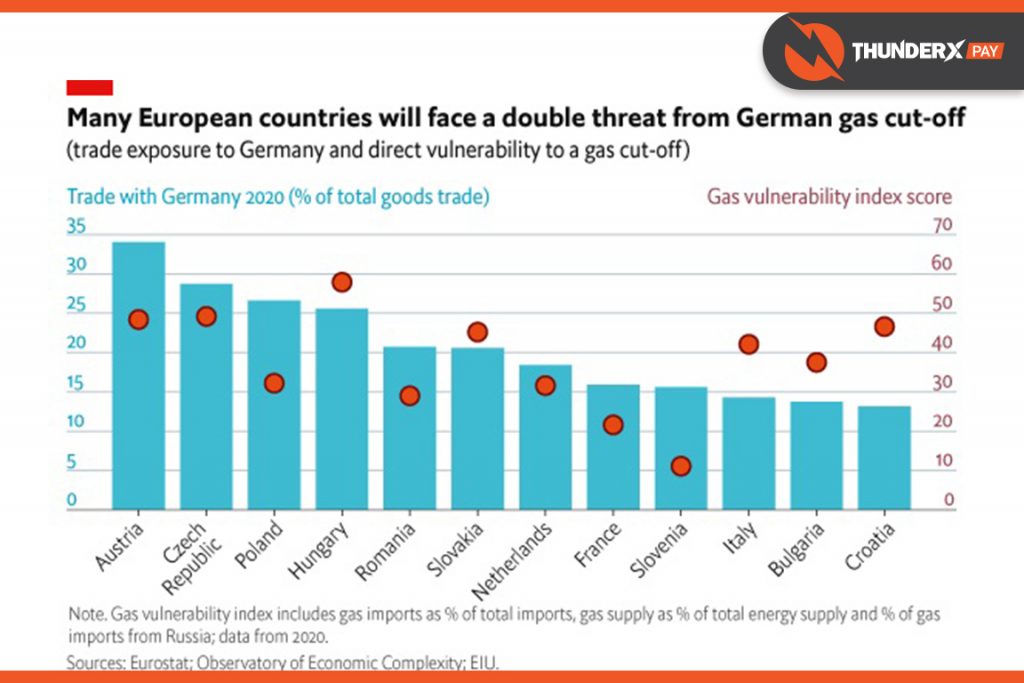

We expect Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia to take the biggest economic hit. Not only will they experience gas shortages, but they are also highly exposed to recession in Germany given strong supply-chain links.

Germany, Austria, and Italy will face gas shortages. We expect rationing in the German industrial sector to have region-wide spillover effects.

Elsewhere in the EU, the main impact will come through high energy prices, falling confidence, and weak external trade. The Baltic states and Bulgaria are particularly exposed. Problems in its nuclear sector make France’s position more precarious than might have been expected.

Next year, Europe will struggle to restock its gas storage without flowing from Russia. The winter of 2023/24 will therefore also be challenging. We expect high inflation and sluggish growth until at least 2024.

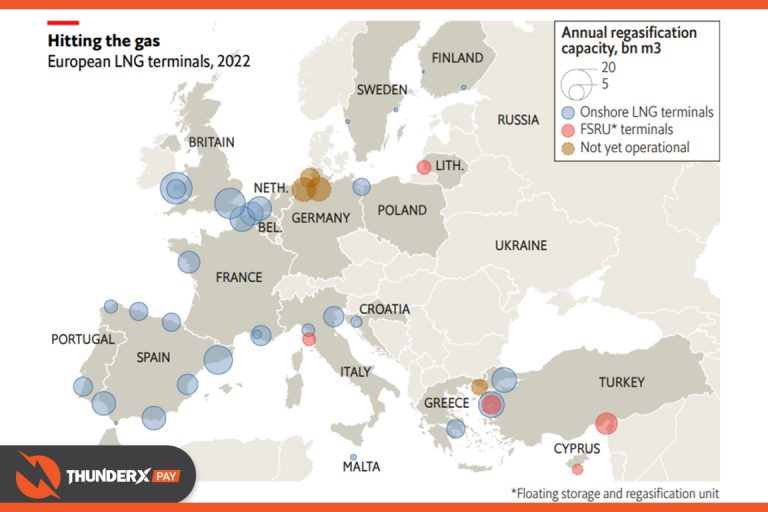

Russia’s aim has been to make a gas supply to Europe as unpredictable as possible and thus undermine economic confidence. We assume that Russia will not increase gas flows to Europe above the current 20% and that cuts to supply may become more severe in the coming months. Efforts to replace Russian gas with other pipelines and liquefied natural gas (LNG) have yielded some results, but cannot go much further in the short term given the limited availability of global LNG supplies and regional regasification terminals. On the demand side, Europe’s gas needs will be suppressed both by the EU’s plan to cut demand by 15% and by the impact on consumers of much higher prices. Still, we expect some countries to be unable to meet their gas needs this winter, with Germany in particular forced to implement industrial rationing.

A cold winter and fraying EU solidarity could make things worse

The economic damage caused by this energy crisis will vary by country. It will also depend on a number of factors that remain uncertain:

How cold will the winter be?

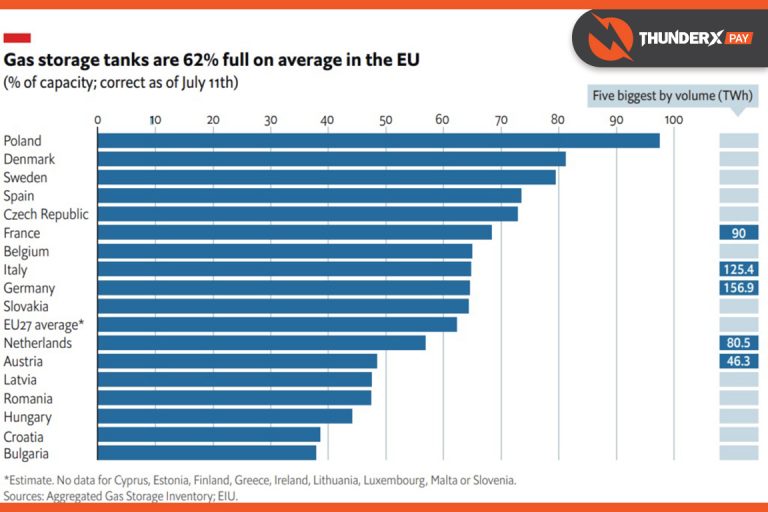

EU winter gas consumption since 2014 has varied between 130bn cu metres and 148bn cu metres. Currently, the EU has 79bn cu metres in storage, just over two-thirds of its total capacity. More countries would face gas shortages in the event of a severe winter.

Will EU solidarity prevail?

Solidarity could break down, not only over demand reduction—a 15% voluntary reduction has been agreed, to become mandatory under certain circumstances, albeit with a long list of opt-outs and incentives—but also over gas sharing between EU member states. Gas sharing would limit the economic pain for the most exposed countries, but agreeing to domestic shortages to help a neighboring country would be unpopular.

How extensive will substitution be?

Reports are emerging of German industrial firms substituting oil or electricity for gas in their processes or importing energy-intensive inputs from elsewhere. The extent and effectiveness of these efforts will have a significant impact on total EU gas demand this winter.

Which sectors will be hit?

EU and firm-level efforts to reduce demand will limit the amount of gas needed this winter, but the most exposed countries will still need to make difficult policy decisions to cut demand further. These could include idling industrial production, imposing price rises, and even outright restrictions on household heating use.

The most at-risk economies: Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia

Central European countries will be the worst hit as they will not only face gas shortages this winter but also suffer from the effects of gas rationing in the German industrial sector, given their integration into German supply chains. Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia have historically relied on Russia for almost all of their gas supply needs, and do not have access to LNG terminals given their landlocked position. Alternative supplies would have to come via countries that are also set to run short of gas (Germany, Italy and Austria), so supply diversification will be limited, especially if EU solidarity frays. Storage rates are comparatively high in the Czech Republic (79%) and Slovakia (70%), although less so in Hungary (51%), but they are insufficient to cover all gas needs. Hungary is hoping to leverage its warm relations with Russia to negotiate new supplies directly via Serbia, but success is not guaranteed. Meanwhile, buying gas on the spot market is very expensive (prices have tripled year on year, and are quadruple those in the US).

The negative economic impact will be felt most in the industrial sector owing to much lower energy efficiency in these countries than the EU average, meaning that firms’ profits will be hit disproportionately by high energy prices. The sectors that will suffer most from gas shortages will be base metals (the largest industrial energy consumer, given gas-fueled furnaces) and chemicals. In addition, suppliers for German industrial firms will face a steep fall in external demand as high prices, falling confidence, and gas rationing choke off German production. In the household sector, policies to shield consumers from rising gas prices are being revised: in Hungary, energy usage above the household average is now being charged at near-market rates, while the Czech Republic will raise end-user prices from September. Slovakia plans to maintain its protections, but energy accounting for a higher than average share of household budgets will also constrain consumer spending. We intend to revise our growth forecasts for these economies by around 4 percentage points, with the hit being predominantly in 2023.

Gas shortages and collateral damage: Germany, Italy, and Austria

Germany is a systemically important economy in the EU—it accounts for a quarter of the bloc’s GDP—so a downturn prompted by gas shortages will have serious spillover effects. The industrial sector accounts for almost 30% of Germany’s GDP, and reliance on Russian gas is high, at 35% (albeit down from a pre-war 55% owing to higher imports from Norway, greater LNG supplies and the restarting of coal-fired power plants). We expect the main damage to the economy to come from energy-intensive industries such as chemicals, steel, glass and fertilizers, which will be the first to face gas rationing. However, higher prices and collapsing confidence are already affecting other sectors such as machinery and automotive manufacturing, with spillover effects being felt in Italy, Austria and central Europe.

Italy also has a large industrial sector (24% of GDP) and high reliance on Russian gas (40%, albeit reduced to 25% owing to higher imports from Algeria, Azerbaijan and elsewhere). However, Italy’s geographical location, with access to other pipelines and LNG infrastructure, means that it is less vulnerable to gas shortages than Germany. Rationing is therefore likely to be limited in Italy, but extensive in Germany and (for similar reasons) Austria. In Italy the productive but energy-intensive mechanical and metallurgy sectors in the north of the country are most exposed to gas shortages; in Austria, the paper industry and steelmakers are the heaviest gas users. We plan to revise down our growth forecasts for these economies by 2-3 percentage points, mainly in 2023.

High prices and secondary effects: Bulgaria, the Baltic states and others

Sky-high energy prices will constrain economic activity across the EU this winter, even in countries that avoid gas shortages. Bulgaria stands out as having particularly high energy intensity—two and a half times the EU average–given very inefficient industrial processes, which will make this costly. The Baltic states also score poorly on this metric, and in all of these countries, energy has a heavy weighting in the consumer price basket, so consumption will be disproportionately affected. Some west European economies that are not exposed to Russian gas but do use gas extensively, and are large enough to affect regional growth rates—such as Spain and the UK—are already experiencing very high prices. We plan to revise down growth in these countries by 0.5-1.5 percentage points.

France is a wildcard: problems with corrosion and scheduled maintenance have taken half of the country’s 56 nuclear reactors offline. The newly nationalised energy company, EDF, plans to reopen enough capacity to have sufficient energy for the winter, but uncertainty is high, and for now, France is having to import more energy than usual, including from the UK. Should this continue, this could divert further gas supplies from their usual markets, and cause shortages even in countries that appear well supplied.

Reducing vulnerabilities in Europe’s energy supply will take time

Short term: we expect a recession in Europe this winter, with the brunt of the economic impact coming in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. An unsupportive global context—given US monetary tightening, China’s growth slowdown and growing investor nervousness—will exacerbate the European downturn.

Medium-term: Replenishing gas storage in 2023 will be difficult given that stocks are likely to be fully depleted this winter. Transitioning away from Russia as an energy source and towards LNG and renewables will take time, while a revival of coal-fired power in some countries will mean a temporary setback to emissions reduction. The winter of 2023/24 is likely to be challenging.

Long-term: the EU’s energy supply will be greener and more resilient (albeit still dependent on imported inputs for renewable technologies). High energy prices will incentivise households and firms to invest in greater energy efficiency. Russia’s geopolitical leverage over the bloc will have been weakened. However, this transition will take several years and will entail considerable economic pain and political turbulence.

Published 22/08/2022

By Michael Saichuk